What else is social studies?

An in-depth look at the anti-bias curriculum.

Prior to my inquiry journey exploring anti-bias and anti-violence curriculum, I understood that prejudicial attitudes were typically passed down generationally within families and were largely the result of ignorance, unfamiliarity, and fear. However, I minimized the role teachers can play in challenging prejudices and curbing their development in such young children: “Both the seeds of respect and the seeds of intolerance are planted when children are very young and nurtured by their experiences and by the attitudes of those around them as they grow” (Partners Against Hate, 2001, p. 25). Similarly, Caryl Stern of the Anti-Defamation League asserts: “No child is born a bigot. Hate is learned and there is no doubt it can be unlearned.” Recognizing that, “after age 9, racial attitudes tend to stay the same unless the child has a life-changing experience,” I now can appreciate the critical importance of specifically teaching the main tenets and emphasizing the essential questions that come with anti-bias curriculum (Aboud, 1988). The essential questions of the anti-bias curriculum that I think are most important, and even incorporate and weave in some of the global education and character formation curriculum that my colleagues discussed, include: How is prejudice different from dislike? How does humanity as a whole benefit when people from all backgrounds are appreciated and included? How does hate influence negative behavior, and why does this harm our global community? Specifically, my inquiry process has led me to generalize, as I expressed in my presentation, that the highest form of anti-bias, the goal teachers should have for all students, is appreciation of differences: “We can learn to respect differences, to see them as a source of strength in our lives and society, even celebrate them” (Anti-Defamation League, 2000).

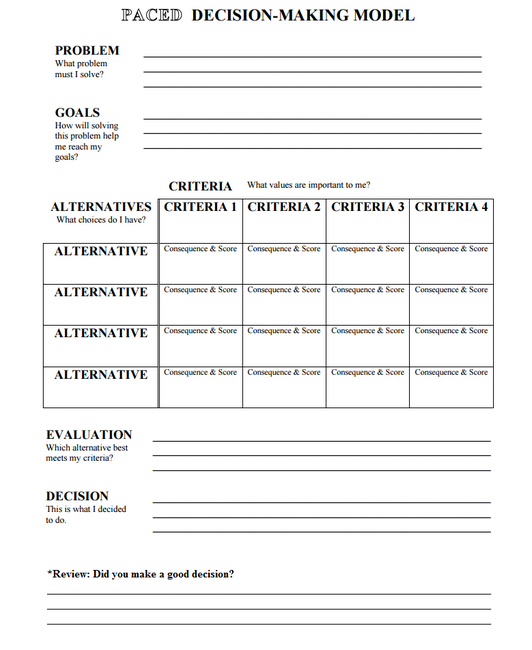

Thus, the anti-bias curriculum goal of leading students to appreciate differences among cultures as opposed to progressing down a continuum of hate that leads to bullying and violence targets the first theme of the National Curriculum Standards for the Social Studies: Culture. Through this curriculum, “students will acquire knowledge and understanding of culture through multiple modes, including fiction and non-fiction, data analysis, meeting and conversing with peoples of divergent backgrounds, and completing research into the complexity of various cultural systems” (NCSS). Similarly, the curriculum integrates New York state social studies and English Language Arts standards across all grade levels. For example, a lesson emphasizing peaceful conflict resolution using a cooperative problem solving method within the social interaction model of instruction targets the Common Core sixth-grade social studies civic participation standard: “Participate in negotiating and compromising in the resolution of differences and conflict; introduce and examine the role of conflict resolution.” Similarly, an anti-bias lesson using multicultural literature as described above would meet the sixth-twelfth grade New York State Common Core Career and College Readiness Standard for Reading 11: Students will “Respond to literature by employing knowledge of literary language, textual features, and forms to read and comprehend, reflect upon, and interpret literary texts from a variety of genres and a wide spectrum of American and world cultures.”

As I explained in detail in my glogster presentation, to target these and other standards, as well as integrate anti-bias curriculum with the disciplines of social studies and other content areas, Partners Against Hate present a plethora of activities for all grade-levels. For kindergarten and first-graders, I would suggest beginning by exploring differences and how they are not essentially bad, which will hopefully help to prevent students from making rash judgments of the unknown later in life. To explore differences, students can read a poem by Nikki Giovanni titled “Two Friends.” By analyzing this poem, students can make the generalization that people can have differences between them and still be friends. Second and third-graders can engage in an anti-bias curriculum research project by interviewing their parents and relatives about their own culture and sharing these stories with the class. The teacher can then promote communication and bridge-building by asking students to identify at least one similarity between their family’s story and a classmate’s family story. Fourth and fifth-graders should focus on exploring the difference between prejudice and dislike and the harmful effects of intolerance and violence. In this way, the anti-bias curriculum can be taught in conjunction with both historical accounts, utilizing primary documents, and present-day accounts, using non-fiction world news articles like those on Newsela, of intolerance and violence. A Partners Against Hate activity (2001, p. 71) that addresses the essential question regarding the difference between prejudice and dislike is to have students act out different scenarios, and then evaluate whether prejudice or simply dislike is present in the conflict.

Other anti-bias activities can be utilized and adapted for students in upper elementary, middle school, and high school grades. An activity with which I was familiar before researching this assignment was having students draw pictures of a certain population before receiving instruction about that group. Typically, many students will draw pictures incorporating stereotypes about the given population. In fact, when I participated in this activity at a recent workshop for teachers and teacher candidates, I was surprised to find that many educated adults still fell into the trap of stereotyping when asked to draw a Native American. While this activity is typically succeeded by a multicultural book about the population to alter students’ perceptions, I think the lesson would be even more powerful if teachers could arrange through Skype for students to interact with the given population from another place in the world or a person of that culture who transcends a negative stereotype, whichever is more appropriate for the given population. Students can then form the generalization that stereotypes inaccurately label individuals, and that they should interact with individuals to learn about them, not trust what they have heard from others.

References

Aboud, F. (1988). Children and prejudice. Oxford, OX, UK: B. Blackwell.

Ada, A.F. (2003). A magical encounter: Latino children’s literature in the classroom. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Dakin, K., & Mateo-Toledo, J. (Speakers) (2015, April 18). Building bridges for our English language learners through the introduction and analysis of Latino literature. 22nd Annual Conference on Literacy. Lecture conducted from Collaborative for Equity in Literacy Learning, Newburgh, NY.

Four Worlds Development Project. (1988). Unity in Diversity Curriculum Guide. Lethbridge: Four Worlds Development Project, University of Lethbridge.

LaRosa, C. (2000). The Anti-Defamation League's hate hurts: How children learn and unlearn prejudice. New York, NY: Scholastic.

National Council for the Social Studies. (1994). Expectations of Excellence: Curriculum Standards for Social Studies. Washington, D.C.: NCSS.

National Council for the Social Studies. (n.d.). National curriculum standards for social studies. Retrieved April 28, 2015, from http://www.socialstudies.org/standards/strands

New York State Education Department. (2011). New York State P-12 Common Core learning standards for ELA and literacy. Retrieved April 28, 2015, from https://www.engageny.org/resource/new-york-state-p-12-common-core-learning-standards-for-english-language-arts-and-literacy

New York State Education Department. (2015). New York State K-12 social studies framework. Retrieved April 28, 2015, from https://www.engageny.org/resource/new-york-state-k-12-social-studies-framework

Partners Against Hate. (2001). Program activity guide: Helping children resist bias and hate. Retrieved April 25, 2015, from http://www.partnersagainsthate.org/publications/pahprgguide302 .pdf