In my previous blog, I described the Cooperative Learning Method of Instruction. However, now having been an active member of a Jigsaw group, I will discuss in further detail a particular Cooperative Learning exercise, Jigsaw.

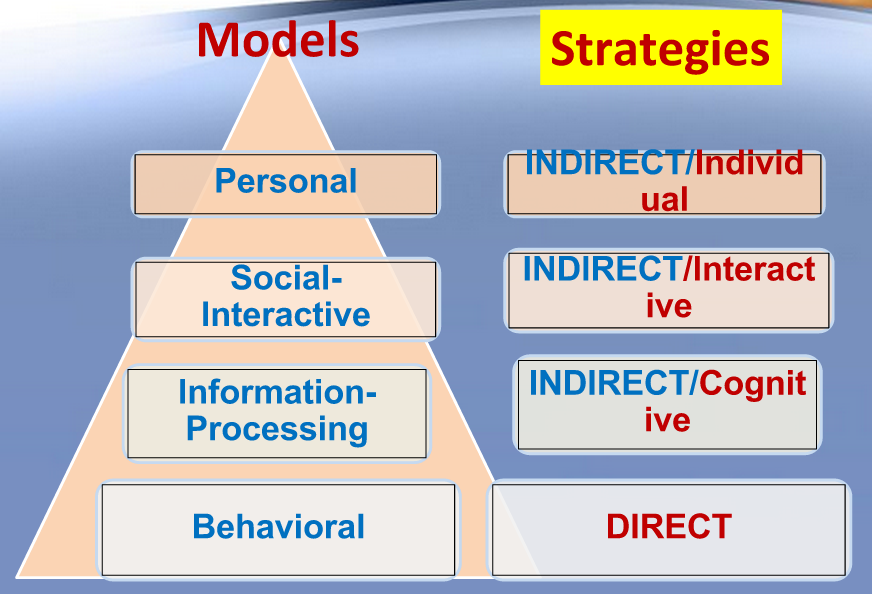

In class, when I was given an opportunity to experience Jigsaw firsthand, the activity was structured differently than what the provided "How to do a Jigsaw- TeachLikeThis" video describes, however, the social learning outcomes were maintained. This shows that small alterations to the structure of a Jigsaw can be actualized while still maintaining the important aims of the lesson (i.e. the five elements of cooperative learning). In our class, two home groups were established, each consisting of three members. The three members then had to divide the required areas of research among themselves for deeper study. At that point, the people in charge of each research topic from both home groups, partnered to become the expert group. For example, utilizing the image above for help, I was in Home Group A with two other people. Then, I became in charge of Research Topic 3. The person in charge of Research Topic 3 from Home Group B partnered with me so that together the two of us formed Expert Group 3. Together, our task was to explore the Cooperative Learning Lesson Plan and more specifically how it differentiates from the Direct Instruction Lesson Plan. To accomplish this exploration, our professor, Dr. Smirnova, already had resources for us to consult which she made available to us electronically. It became our job to analyze these resources and then create our own presentation, in the form of a direct instruction lesson, which we would present to the entire class. This is a slight derivation from traditional jigsaw in which, as discussed in the video, students are only responsible for presenting the information to their original home group after having worked in expert groups. Then, teachers may elect to have the home groups deliver presentations to the entire class or may design another form of assessment to ensure students achieved the learning outcomes.

In class, when I was given an opportunity to experience Jigsaw firsthand, the activity was structured differently than what the provided "How to do a Jigsaw- TeachLikeThis" video describes, however, the social learning outcomes were maintained. This shows that small alterations to the structure of a Jigsaw can be actualized while still maintaining the important aims of the lesson (i.e. the five elements of cooperative learning). In our class, two home groups were established, each consisting of three members. The three members then had to divide the required areas of research among themselves for deeper study. At that point, the people in charge of each research topic from both home groups, partnered to become the expert group. For example, utilizing the image above for help, I was in Home Group A with two other people. Then, I became in charge of Research Topic 3. The person in charge of Research Topic 3 from Home Group B partnered with me so that together the two of us formed Expert Group 3. Together, our task was to explore the Cooperative Learning Lesson Plan and more specifically how it differentiates from the Direct Instruction Lesson Plan. To accomplish this exploration, our professor, Dr. Smirnova, already had resources for us to consult which she made available to us electronically. It became our job to analyze these resources and then create our own presentation, in the form of a direct instruction lesson, which we would present to the entire class. This is a slight derivation from traditional jigsaw in which, as discussed in the video, students are only responsible for presenting the information to their original home group after having worked in expert groups. Then, teachers may elect to have the home groups deliver presentations to the entire class or may design another form of assessment to ensure students achieved the learning outcomes.

Finally, through the presentations, expert groups shared with the class in-depth analyses of the elements of cooperative learning and the cooperative learning lesson plan. Having learned this information, I can confidently say that Jigsaw aligns with the elements of cooperative learning in the following ways:

1. Positive Interdependence: Students have to rely upon their group members to learn the necessary information. The only way they are supposed to be able to gain all of the knowledge that will be assessed later is by communicating with group members.

2. Individual Accountability: When split into expert groups, students are aware that they alone are responsible for ensuring that their home group receives the information they uncover. Additionally, by making students aware that they will be assessed again individually following the Jigsaw activity, they know that they must have a firm grasp on all the material and cannot rely on teammates to "bail them out."

3. Face-to-Face Promotive Interaction: Students are forced to talk to one another to ensure that everyone receives all of the necessary information. Every student is given a sense of confidence for the aspect that he or she will teach to the rest of the group. Students are then able to practice how to express ideas clearly to peers and to check that their peers understand them through conversation.

5. Group Processing: Teachers have to ensure that group processing occurs after the Jigsaw Activity. In my personal experience with Jigsaw, this was the element that was most lacking as time constraints prevented our class from discussing what we could improve upon for the next experience. However, group processing can easily be incorporated into the activity especially at the end when the home groups have come back together. After discussing content, they can discuss what information was easily understood and remembered, but also where there were difficulties in teaching one another and make suggestions as to how they can improve for the next experience.

Additionally, Christine and I were in charge of teaching the Cooperative Learning Lesson Plan to our classmates. Knowing that I would have to present the information, I dedicated time to researching and reviewing the material to ensure that I understood it fully and would be prepared to entertain any questions from my peers.

Implications for My Future Classroom

Implications for My Future Classroom

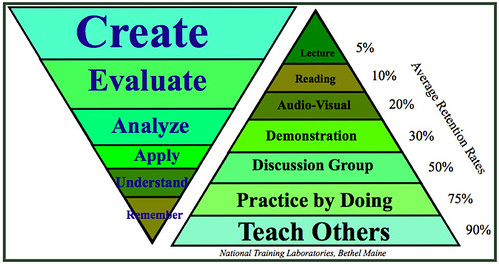

When my professors utilize active learning exercises, I know that I have to prepare differently than with passive learning exercises. With this Jigsaw activity, I had to ensure that I truly had mastered the material, because otherwise I would not have been able to deliver a presentation of value to the rest of the class. If instead, my professor had asked me to read an article on how to create a Cooperative Learning Lesson Plan, I would have read the article and came away with a sense of how to do so. In the next class, I would have reiterated the main points. However, with this passive assignment, I would certainly not have gained as deep of a grasp as when I am focusing for the purpose of teaching others, and more importantly, I would not have retained the material long-term. Understanding how my approach to the material changed with the type of assignment and the realities of the research associated with the learning pyramid, I will want to use Jigsaw and other active learning activities in my future classroom so that my students can truly master both academic and social learning outcomes.

Works Cited

5 Basic Elements - Cooperative Learning. (n.d.). Retrieved February 9, 2015, from https://sites.google.com/a/pdst.ie/cooperative-learning/5-basic-elements

How to do a Jigsaw - TeachLikeThis. (2013, October 14). Retrieved February 9, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfSKkCVFXfM

How to do a Jigsaw - TeachLikeThis. (2013, October 14). Retrieved February 9, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfSKkCVFXfM

Puzzled jigsaw puzzle. (n.d.). Retrieved February 9, 2015, from http://thejigsawpuzzles.com/People/Puzzled-jigsaw-puzzle